The Spanish Civil War (1936 – 1939) has come to symbolize the clash between the ideologies of liberalism, socialism and communism versus conservatism, traditionalism and fascism. Spain, at the dawn of the 20th century, was caught in a crisis of identity and purpose. The once-mighty Spanish Empire was no more. Most of the countries of Latin America had become independent by 1821; and, in 1898, Spain’s few remaining colonies, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, were lost to the US in the Spanish-American War. Only a small stretch of North Africa, Spanish Morocco, was left of the empire that once ruled half the world.

The origins of Spain’s decline were the subject of intense debate and controversy. Some held that Spain had strayed too far from her traditional Catholic values, while others believed that Spain had failed to change with the times and enter the modern world. A division between traditionalists and modernizers polarized Spanish society.

Moreover, internal Spanish contradictions fueled the flames: a poor, underdeveloped, agricultural south versus a vibrant, modern, industrial north and east; radical socialist and anarchist parties and unions versus the established elites of church and aristocracy; tension between the national center and the aspirations of regional minorities and ethnic groups, and an increasing demand for democracy and liberalism versus monarchy and military dictatorship.

General Primo de Rivera’s authoritarian regime, supported by the Spanish King Alfonso XIII, kept a lid on these contradictions between 1923 and 1930. However, Primo de Rivera’s pragmatic approach was deemed “too soft” by some on the right and he was forced to step down. With the strong hand lifted, matters in Spain started to boil over.

Faced with elections where republican, liberal and socialist parties won a landslide victory, King Alfonso abdicates – later he commented that he had the fate of Russian Tsar in mind. The very next day, April 14, 1931, the Spanish Republic was declared.

Headed by moderate liberals, the new Republic immediately embarked on a policy of social reform. Land reform is undertaken, minority rights and languages are recognized and women are granted the vote. Public education is taken out of the hands of the Catholic Church and secularized. These reforms sparked sharp opposition from conservatives, the Church and the military.

An escalating cycle of political violence gripped Spain as strikes, riots and assassinations spread. The breaking point was reached on January 15, 1935, when the Popular Front, a coalition of liberal, socialist and communist parties, was elected into office.

Emilio Mola, an army general, began to organize a conspiracy to overthrow the Republic. Secretly, Mola gains the support of the Church hierarchy and leading military figures such as Spain’s youngest general Francisco Franco. Mola also secures the help of Jose-Antonia Primo de Rivera, son of the ex-dictator and leader of Spain’s blue shirt-wearing fascist party, the Falange.

Mola plans on a simultaneous military rising in all of Spain’s major cities that will overthrow the Republic and roll back the liberal reforms. As the parts of the conspiracy fall into place, Mola waits for an opportunity.

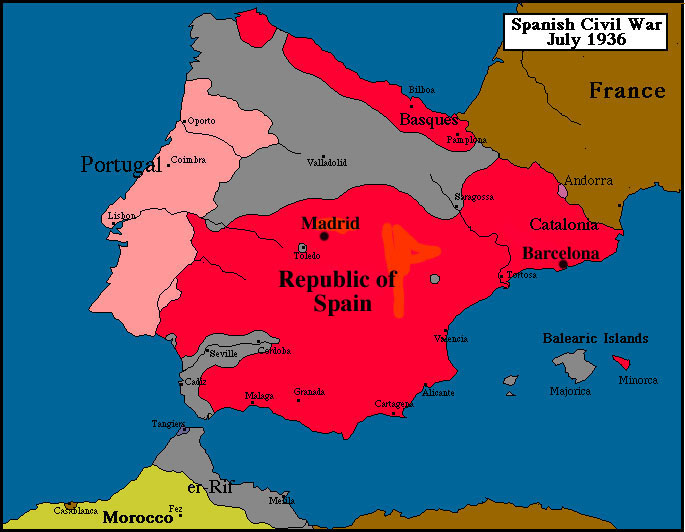

He did not have long to wait – the moment came when escalating battles between left and right led to the murder of a socialist policeman and the retaliatory killing of a conservative politician. The chaos following the killings provided Mola with the necessary momentum. On the night of July 17, 1936, military units all over Spain rose in rebellion. Franco’s Moroccan troops are airlifted to southern Spain. But the conspirators hadn’t counted on two things: many army units refused to join the rising and remained loyal to the Republic; and the spontaneous arming of the people under anarchist, socialist and communist leadership.

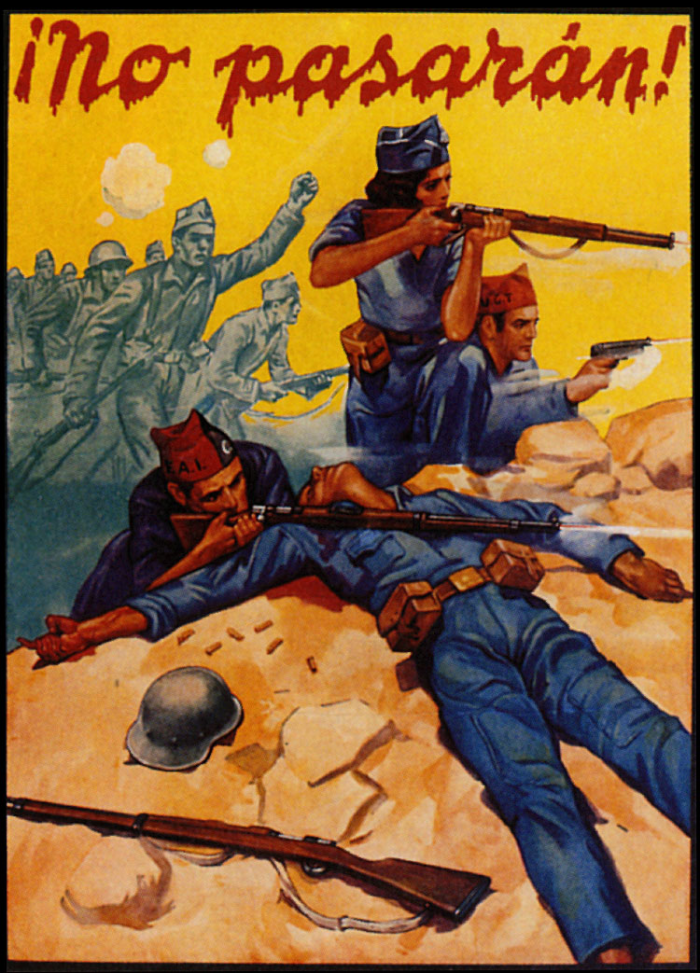

Street fighting is particularly fierce in Madrid, where the communist leader Dolores Ibarruri will make the passionate speeches urging resistance to the military coup that will earn her the moniker, “La Pasionaria” (the Passion flower). Her rallying cry of “No pasaran!” (“They will not pass!”) became an international catchphrase as the rebellion in Madrid is put down.

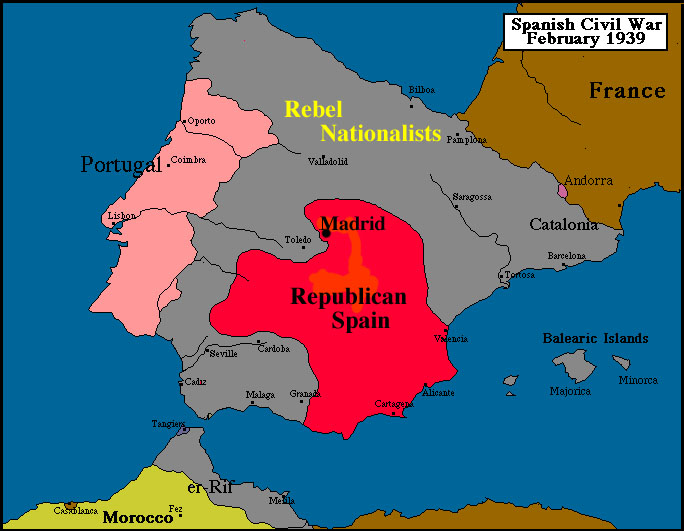

Spain was divided into two main territories: the area held by the military and their sympathizers (the Nationalists) and that held by those loyal to the Spanish Republic (the Republicans). The Spanish Civil War has begun; it will continue for three years.

Needing a front man, Mola names Franco the Caudillo – an archaic Spanish term for a popular leader, roughly equivalent to the Italian Duce and the German Fuhrer – of the Nationalist cause. The image will become reality a year later when Mola’s sudden death in an airplane crash and Primo de Rivera’s execution in the Republican zone leaves Franco as the supreme Nationalist chieftain. The eyes of the world focus on the fighting in Spain.

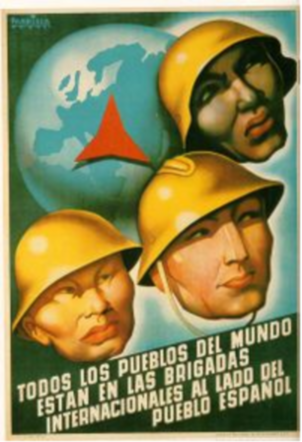

An international Non-Intervention Committee is formed that denies arms and supplies to either side. “Non-intervention” becomes a farce as Franco asks for and receives arms, money, and troops from Mussolini and Hitler. Meanwhile, the Republic is left isolated and alone. Only two countries support the Republic: Mexico and the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union mobilizes international public opinion in support of the Republican cause. The Republic desperately fights to survive, relying on the enthusiasm of volunteer workers’ militias, as the Nationalists press on. From an unexpected source, help then arrives from all over the world.

In a romantic manner, the plight of Republican Spain captured the imagination of the world. Thousands arrived from Cuba and Canada, the United States and France, Britain and Peru, even escaped anti-fascists from Italy and Germany to volunteer to fight on behalf of the Republic. These are the celebrated International Brigades.

Thanks to the arrival of the Internationals, the Nationalist advance is halted. But the flow of German and Italian aid – including the German elite Condor Legion air squadron – and the steady loss of farmland to the Nationalists reverses the tide.

The Nationalists introduce total war to Spain: the saturation bombing of cities (thanks to the Condor Legion), and brutal reprisals against civilians. Despite the determined resistance of the Republicans, the Nationalists occupy more and more territory; and soon shortages, famine and disease begin to plague the Republicans. Disunity on the Republican side, especially destructive ultra-leftism on the part of the anarchists and Trotskyites, wastes valuable time, effort and resources on faction fighting; a fact of which Franco took full advantage.

Weary, starved and lacking in fuel and arms, the Republic is continuously whittled away. In February of 1939, Franco’s Nationalists reach the sea, completely surrounding and cutting off the Republic. The next month, the Republic surrenders. The Spanish Civil War is over. Franco will establish a personalist, Catholic-Fascist dictatorship that will rule Spain until 1976. As for the rest of the world, it hardly has chance to catch its breath—because of the failure to stop the rise of fascism, in six months, World War II began.

Categories: History, International, Revolutionary History, Spain, Workers Struggle, World History

Juan Perón and Social-Fascism in Argentina

Juan Perón and Social-Fascism in Argentina

Tell us Your Thoughts