“All I know is that D’Aubuisson is a free enterprise man and deeply religious.” – Jesse Helms

“[T[ake care of this archbishop, these Jesuits, these other priests and especially these foreigners who are ruining the minds of our children. And if the gringos want to help the communists and cut military aid, we didn’t need military aid in 1932. If we had to kill 30,000…in 1932 [during “La Matanza” or “The Slaughter” where farmers and natives were killed during a revolt against the fascist government], we’ll kill 250,000 today.” — Roberto D’Aubuisson telling a rally of supporters what they would have to do after winning.

“The major has lived, step by step, the process of pacification of the country.” — Armando Calderon Sol on D’Aubuisson.

Introduction

Who is this handsome man pictured above, waving his clenched fist at someone off-camera and with his big mouth wide open? It’s Roberto “Blowtorch Bob” D’Aubuisson, given such a charming name for his penchant for using blue-hot butane torches on his victim’s limbs and genitalia during the torture sessions of suspected leftists, liberals, communists and labor leaders. He became infamous in his home country of El Salvador during the civil war against the leftist FMLN movement for leading CIA-trained death squads that carried out scores of massacres. He was trained at the infamous “School of the Americas” in 1972.

The Hitler-loving D’Aubuisson was quoted as saying, “You Germans were very intelligent. You realized that the Jews were responsible for the spread of Communism and you began to kill them.” A former National Guard and founder of the ultra-conservative Nationalist Republican Alliance or ARENA party, it wasn’t popular support but rather support from abroad that was the true source of his power. Robert E. White, Jimmy Carter’s ambassador to El Salvador, called him a “pathological killer” on American national television.

There is no area of the Cold War quite as consistent as the United States’ support for jackbooted anti-communist dictators and neo-fascist mass murderers such as ole’ Bob. His victims were by no means limited to left-wing categories—other undesirables in Bob’s way to neo-liberal privatized power were civilians, villagers, priests, nuns, women, children, infants and pretty much anyone unlucky enough to get between his death squads and supporters of the left-wing in El Salvador.

Despite this, D’Aubuisson and many others like him received exorbitant amounts of financial support and training from the United States. As the New York Times stated,

“In El Salvador, American aid was used for police training in the 1950’s and 1960’s and many officers in the three branches of the police later became leaders of the right wing death squads that killed tens of thousands of people in the late 1970’s and early 1980’s” (1).

A favorite of wealthy landowners and rich capitalists, D’Aubuisson first became known through nighttime television broadcasts where he accused civilian leaders, teachers and unionists of being communist subversives (the mutilated bodies of some were later found). D’Aubuisson studied intelligence and security in Virginia and New York, and in 1970 and 1971 studied at the International Police Academy in Washington. The academy was later closed after members of Congress said it had taught techniques of torture.

D’Aubuisson died in 1992 from esophageal cancer at age 48. He was never tried for any of his crimes. In fact, he was flown into the United States for medical treatment several times. His story is far from exceptional in Latin America, where US imperialism has run amok for decades under the convenient guise of “counter-insurgency” programs.

El Salvador from the 1800’s to the 1980’s: A Neo-Colony Ready for Change

“EL SALVADOR is one of the poorest countries in the western hemisphere, with low per capita income, chronic inflation, and high unemployment. The nation’s economy traditionally depends heavily on coffee, although today (2006) remittances from over 2,000,000 Salvadorans working abroad are a major source of income. Despite several attempts at land reform, 1 percent of the landowners still control more than 40 percent of the arable land. The colón was the basic monetary unit (8.7 colones equal U.S. $1), but in 2001 the U.S. dollar was adopted as equal legal tender, and now colones are seldom used” (2).

After the 19th century, El Salvador’s economy was largely based on the colonial model, specializing in cash crops like coffee, an extension of its use by the Spanish Empire as a colony for the export of indigo (an ingredient used for dye), which had diminished by the mid-19th century and was replaced by coffee in 1870. By the 1880’s, coffee exports accounted for 95% of El Salvador’s income. Its unequal distribution of land ownership was notable—the economy was entirely based on large plantations owned by a tiny wealthy elite. These cash crops would be harvested and prime for export into larger dominating countries. The colonial cash crops produced by El Salvadorian plantations soon expanded to include sugar and cotton.

The ruling families of El Salvador, called “the Fourteen Families” operated almost as feudal lords, having the Constitution authored in their favor throughout the 1800s and maintaining a super-majority power in the national legislature. In 1824, the legislature had 70 seats, 42 were set aside for landlords, and the President was exclusively chosen from this same landed elite. This oligarchy ruled the country and controlled most of the land during the 19th and 20th centuries.

El Salvador’s colonial economy made it vulnerable to capitalist economic crisis due to the lack of subsistence farming, and when the export price of coffee dropped 54% between 1928 and 1931, the misery was mainly felt by the laboring masses. Wages were cut severely even as the price of foodstuffs skyrocketed. Because of the hunger and frustration increasing numbers of people flocked to organizations such as the Communist Party of El Salvador, the Anti Imperialist League and the Red Aid International.

In 1912, President Manuel Enrique Araujo founded the National Guard, which largely consisted of recruited officers of the former Spanish Civil Guard. They were employed as rural police throughout the country.

Augustín Farabundo Martí Rodríguez, known to history as Farabundo Martí, soon emerged onto the political scene. An educated man inspired by the writings of Karl Marx and a member of the Central American Socialist Party with ties to the Regional Federation of Salvadoran Workers, Martí sought to foment popular rebellion against the oppressive oligarchic government on behalf of the working poor. He was jailed and exiled several times by the authorities for his popularity.

11 Dec 1983, San Salvador, El Salvador — San Salvador, El Salvador: U.S. Vice President George Bush (left) raises his glass to El Salvador’s President Alvaro Magana in a toast offered at dinner in Bush’s honor. During the toast Bush relayed President Reagan’s deep concern over the continued violence and murder committed by right wing death squads. The dinner was attended by El Salvador’s military and political leaders following Bush’s trip to Argentina. — Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

La Matanza : Indigenous Genocide

After a coup in 1931, Araujo was overthrown and the military installed Maximiliano Hernández Martínez, Araujo’s vice president. An ardent fascist, Maximiliano Hernández Martínez lavishly admired Adolf Hitler and barred Jews, Palestinians and people of African descent from entering El Salvador. Candidates of local communist and leftist organizations who had won municipal offices in western El Salvador were subsequently barred from assuming office. In 1931, Martí returned to El Salvador and started a guerrilla revolt of indigenous farmers.

Maximiliano Hernández Martínez organized a massive campaign of violence in 1932, eventually ending with a genocide against indigenous people who were collectively blamed for the uprising. Over 30,000 indigenous people were murdered by the government. Proportional to the population of El Salvador, in order to reach this same percentage, 60 million U.S. citizens would have to be killed. Anyone who looked like a Native, dressed like one or spoke Nahuatl was killed by the army. To this day, the Native culture of El Salvador has been wiped out by the genocide – many indigenous, particularly the Pipil group, adopted Western dress, abandoned their culture and their language and intermarried with members of non-indigenous groups in order to avoid the violence.

Almost all of these killings were committed by government forces, since the communist insurgency caused no more than 30 civilian deaths. Many infamous massacres happened, including an incident where Martínez invited rebels to a town square, promising open discussion and pardons for those involved in the peasant uprisings. When they arrived, many thousands of them were immediately fired upon and killed. The violence spread everywhere:

“Roadways and drainage ditches were littered with bodies,” writes Raymond Bonner. “Hotels were raided; individuals with blond hair were dragged out and killed as suspected Russians. Men were tied thumb to thumb, then executed, tumbling into mass graves they had first been forced to dig.” (3).

This period became known as La Matanza (The Slaughter). During these events, the United States supported General Martínez, stationing warships off the coast, ready to assist him with Marines in case he suffered any opposition.

In addition to the mass murder, President Hernández Martínez had Farabundo Martí shot after a show trial. Farabundo Martí is now a martyr for the Salvadoran Left. Feliciano Ama, an indigenous leader, was hanged in the city of Izalco. This event was shown on issued postage stamps at the time. Accounts of the mass murder and genocide were taken from El Salvador’s National Library and burned, to be replaced with documents portraying Hernández Martínez as the “savior of El Salvador,” protecting the people from “vicious communists and barbaric Natives.”

Hernández Martínez was finally overthrown in 1944. He fled to Honduras, where he lived in exile until he was stabbed to death by his driver, Cipriano Morales, the son of one of many murdered by his dictatorship.

The 1931 coup and subsequent genocide was the start of over fifty years of military rule in El Salvador, marked by an endless string of military coups and clashes between rebel guerrilla and government forces. The precedent set by La Matanza of a violent oligarchic military junta organizing a brutal campaign to suppress a leftist guerrilla movement would soon be echoed in the later 20th century during the height of the Cold War.

This similarity would be highlighted by the ominous name of one of the many right-wing death squads operating in El Salvador responsible for the brutal killing of many democrats, leftists, clergy and civilians throughout the country — the Maximiliano Hernández Martínez Brigade.

Origins of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN)

As seen above, imperialist involvement in El Salvador and the propping up of its military dictatorship already had a long history by the time the FMLN appeared on the scene.

“As far back as 1964, the CIA helped form ORDEN and ANSESAL, two paramilitary intelligence networks that developed into the Salvadoran death squads. The CIA trained ORDEN leaders in the use of automatic weapons and surveillance techniques, and placed several leaders on the CIA payroll. The CIA also provided detailed intelligence on Salvadoran individuals later murdered by the death squads. Even after a public outcry forced President Reagan to denounce the death squads in 1984, CIA support continued” (4).

Soon however, popular discontent again arose against the oligarchs and the military. The Oxford Companion to American Military History sheds some light on the situation under the entry regarding U.S. military involvement in El Salvador:

“In the late 1970s, various small left wing insurgent groups allied to ‘popular organizations’ of peasants, students, and slum dwellers began challenging the military government” (5).

12 Feb 1980, San Salvador, El Salvador — The dead bodies of men, following a demonstration of the left wing student organization MERS. The demonstration ended in a gunfight which killed 20 people. — Image by © Michel Philippot/Sygma/CORBIS

One of these popular organizations, the FMLN, was formed on October 10, 1980. It was an umbrella group which included in its ranks such leftist guerrilla organizations as the Bloque Popular Revolucionario (BPR) and its armed wing Fuerzas Populares de Liberación (FPL) “Farabundo Martí”, the Partido Comunista Salvadoreño (PCS) and its armed wing Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación (FAL), the Partido de la Revolución Salvadoreña (PRS) and its armed wing Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo (ERP) (El Salvador), the Resistencia Nacional (RN) and its armed wing Fuerzas Armadas de la Resistencia Nacional (RN-FARN), and the Partido Revolucionario de los Trabajadores Centroamericanos (PRTC) and its armed wing Ejército Revolucionario de los Trabajadores Centroamericanos (ERTC).

Later, it would expand to include other left-wing High School student movements such as the Movimiento Estudiantil Revolucionario de Secundaria (MERS), the Brigadas Revolucionarias de Estudiantes de Secundaria (BRES), the Ligas Populares de Secundaria (LPS), the Asociación de Estudiantes de Secundaria (AES), and the Acción Revolucionaria de Estudiantes de Secundaria (ARDES). It would also include movements among Universirty students such as the Asociación General de Estudiantes de la Universidad de El Salvador (AGEUS) and the Frente Universitario de Estudiantes Revolucionarios “Salvador Allende” (FUERSA).

After many splits and factional clashes the above groups united in 1980. Despite the claims of the U.S. government, and despite the inspiration of the Cuban Revolution to the FMLN, the Cuban and Soviet governments were not significantly responsible for financially and materially backing the FMLN. This unity among rebel groups was primarily motivated by the history of social unrest in the country. Since the early 20th century, guerrilla groups had consistently existed in El Salvador and fought the government, which soon reinstated death squads to deal with the rebel forces.

1979-1980: Changes in Military Government

IIn 1979, the Revolutionary Government (Spanish: Junta Revolucionaria de Gobierno, JRG), a five-man military junta led by two colonels, Adolfo Arnaldo Majano Ramos and Jaime Abdul Gutiérrez Avendaño, and possessing three civilians, took power in a coup against President Carlos Humberto Romero. The junta made promises to improve living standards, initiate a land reform and nationalize the banks and sugar and coffee production. Although the Salvadorian military was generally seen as a right-wing force in politics, the JRG promised left-wing reforms in order to quell rebellion but failed to deliver.

Contradictions soon emerged in the Revolutionary Government, especially between Colonel Majano and Colonel Gutiérrez. By January 5, 1980 all civilian members resigned from the junta, which then became the Second Revolutionary Government Junta. Again on March 3rd of 1980, one of the replacements Héctor Miguel Dada Hirezi resigned over the violence.

20 Aug 1980, San Salvador, El Salvador — The bodies of two young girls lie along highway to the international airport, about 15 kilometers from the capital. They are presumed to be the latest victims of rightist death squads. — Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

He was then replaced by José Napoleón Duarte, a founding member and Secretary General of the opposition Christian Democratic Party (PDC) since 1960. The government became the Third Revolutionary Government Junta. Finally, Colonel Majano, who had consistently been the supposed “left-wing” of the military junta, was expelled and thrown into exile. José Napoleón Duarte became the head of the junta and Colonel Gutiérrez became Vice President. José Napoleón Duarte was named the first civilian president of the country in December of 1980.

The government began to lose control of the country due to continued uprisings and opposition. In order to combat mass protests against the oligarchy, members of the Salvadorian military and affiliated paramilitaries, or the death squads, continued to commit atrocities throughout Duarte’s reign while he appeared to keep his hands clean. In reality, the “moderate” Duarte, a US favorite, was a puppet of the military junta who served his function of securing them US aid so they continue to massacre civilians.

December 1980, El Salvador — Armed soldiers burn the bodies of guerrilla fighters killed in a confrontation. — Image by © Alain Keler/Sygma/Corbis

The Beginnings of the Salvadorian Civil War: the Rio Sumpul Massacre

“On March 7, 1980, two weeks before the assassination [of Oscar Romero], a state of siege had been instituted in El Salvador, and the war against the population began in force (with continued US support and involvement). The first major attack was a big massacre at the Rio Sumpul, a coordinated military operation of the Honduran and Salvadoran armies in which at least 600 people were butchered. Infants were cut to pieces with machetes, and women were tortured and drowned. Pieces of bodies were found in the river for days afterwards. There were church observers, so the information came out immediately, but the mainstream US media didn’t think it was worth reporting.

Peasants were the main victims of this war, along with labor organizers, students, priests or anyone suspected of working for the interests of the people. In Carter’s last year, 1980, the death toll reached about 10,000, rising to about 13,000 for 1981 as the Reaganites took command” (6).

January 1981, El Salvador — El Salvadorian Army Searches for Guerrillas — Image by © Alain Keler/Sygma/Corbis

The massacre was committed by units of Military Detachment No. 1, the National Guard and the CIA-backed paramilitary Organización Nacional Democrática (ORDEN).

At the time the war was raging in his homeland, Duarte visited the United States in order to seek support against the leftist insurgents, who were at different times and places falsely claimed to be backed by the Soviet Union, Sandinista Nicaragua, Castro’s Cuba and the Warsaw Pact. President Jimmy Carter, after seeing the toppling of the military dictatorship of Somoza in Nicaragua, decided that there was a “moral imperative” to back the military dictatorship against the rebels. The regime of Duarte immediately received military aid and financial backing from the United States. An advisor to Carter said:

“The domino theory lives…No President wants to lose something to communism on his watch” (7).

The FMLN finally fought back by launching their first armed struggle on January 10, 1981, and quickly gained control over large tracts of territory in Morazán and Chalatenango, which they would keep throughout the war.

The Salvadorian Civil War had begun. It was one of the longest and bloodiest civil wars in Latin America, lasting until 1992. The conflict against the government propped up with US money and military advisers would kill many thousands and drive one million people, or one-fifth of El Salvador’s population, from their homes in terror.

Demonstrators, carrying banners with images of Roman Catholic Archbishop Oscar Arnulfo Romero, march during a rally marking the 29th anniversary of his death in San Salvador, Saturday, March 21, 2009. Romero was assassinated in 1980 after he urged the military to halt death squads that killed thousands of suspected guerrillas and opponents of the El Salvador’s government. (AP Photo/Edgar Romero)

The Assassination of Archbishop Oscar Romero

“When the church hears the cry of the oppressed it cannot but denounce the social structures that give rise to and perpetuate the misery from which the cry arises.” – Oscar Romero

“A church that suffers no persecution but enjoys the privileges and support of the things of the earth – beware! – is not the true church of Jesus Christ. A preaching that does not point out sin is not the preaching of the gospel. A preaching that makes sinners feel good, so that they are secured in their sinful state, betrays the gospel’s call.” – Oscar Romero

“The church would betray its own love for God and its fidelity to the gospel if it stopped being . . . a defender of the rights of the poor . . . a humanizer of every legitimate struggle to achieve a more just society . . . that prepares the way for the true reign of God in history.” – Oscar Romero

One of the catalysts for escalation of the war was the famous assassination of Óscar Arnulfo Romero, two weeks after José Napoleón Duarte became the leader of junta. The fourth Archbishop of San Salvador, Romero was initially appointed as Archbishop on February 23, 1977. He was a predictable and orthodox bookworm, elected as a compromise candidate by conservative fellow bishops. He had a reputation for a pious and timid approach, which caused some dissent among priests espousing liberation theology, who felt his appointment would undermine the Catholic clergy’s commitment to the poor. The people of El Salvador never expected him to come out on their side. The Salvadorian Civil War would soon have a deep impact on Romero, however.

On March 12th, 1977, Rutilio Grande García, a Jesuit priest and a very close friend of Romero’s, was assassinated along with Manuel Solorzano, 72, and Nelson Rutilio Lemus, 16, by machine gun fire. It was well-known that landowners saw Grande’s work among the peasants as a threat to their power, as he was a leading champion of the poor, a promoter of liberation theology and had been deeply involved in creating groups among the campesinos. He had been targeted for stating that the big landowners’ dogs ate better the campesino children whose fathers worked in their fields.

After the killing of Father Grande, Romero went to the church to view the three bodies and spent many hours praying and hearing the stories of the suffering farmers. Romero stated, “When I looked at Rutilio lying there dead I thought, ‘If they have killed him for doing what he did, then I too have to walk the same path.'”

The next morning, Romero announced that he had changed his stance toward the government – as Archbishop he would no longer attend any state functions or meet with the president. The murder of Grande would never be investigated by the government, despite Romero’s repeated pleas to do so. From that time on, Romero’s rhetoric became more revolutionary, speaking out against poverty, social injustice, assassinations and torture by government forces. “Those who work on the side of the poor suffer the same fate as the poor,” he said. He stopped the building of a cathedral, and said it would not resume until the war was over and the hungry were fed. He met Pope John Paul II and criticized his support of the military government despite its wholesale massacres and violations of human rights.

On March 14, 1977, Romero publically stated in two newspapers that his view of the murders was that Father Rutilio Grande was killed for political reasons, for raising the spirit of the people. The following Sunday, Romero canceled Masses throughout the archdiocese in protest. He instead held Mass in one small cathedral in San Salvador, where he was joined by 150 priests and over 100,000 people, who listened eagerly to Romero’s calls to end the violence. Romero soon earned a reputation as the “bishop of the poor.”

“In 1980 the war claimed the lives of 3,000 per month, with cadavers clogging the streams, and tortured bodies thrown in garbage dumps and the streets of the capitol weekly. With one exception, all the Salvadoran bishops turned their backs on him, going so far as to send a secret document to Rome reporting him, accusing him of being ‘politicized’ and of seeking popularity.” (10)

In an attempt to defend the Salvadorian people, he called for international intervention to prevent murders by security forces. Romero also criticized the United States for sending the junta aid, and wrote to Jimmy Carter in February of 1980, saying that further aid would “undoubtedly sharpen the injustice and the repression inflicted on the organized people, whose struggle has often been for their most basic human rights.” He added, “”You say that you are Christian. If you are really Christian, please stop sending military aid to the military here, because they use it only to kill my people.” The President ignored his plea and continued to pour 1.5 million dollars of aid a day into El Salvador for years, as did his successors. His letter never received a response.

“I have often been threatened with death,” he had told a Guatemalan reporter two weeks before his assassination. “If they kill me, I shall arise in the Salvadoran people. If the threats come to be fulfilled, from this moment I offer my blood to God for the redemption and resurrection of El Salvador. Let my blood be a seed of freedom and the sign that hope will soon be reality.”

“Romero had the only uncensored voice in San Salvador, a small radio station. It broadcast the names of people who were missing. It would happen that a man would be taken off and never heard from again, and his family would ask a priest for help in tracing him. These things soon wound up in the archbishop’s lap. He wanted answers, why people were arrested and what was happening to them.” (8).

Romero associated daily with hundreds of the poor, traveled the countryside and assisted the suffering. Many times he drove out to a garbage dump where bodies were often taken by government death squads after torture and execution. He would dig through the garbage to find the bodies, often accompanied by friends or family members. “These days I walk the roads gathering up dead friends, listening to widows and orphans, and trying to spread hope,” he said.

Weeks after writing the letter to Jimmy Carter, Romero leaped headfirst into the fire – on March 23rd, 1980, one day before his murder, he called for revolutionary defeatism among the Salvadorian military, asking soldiers in the National Guard, the police and the military to refuse to obey orders. “Brothers, you are from the same people; you kill your fellow peasant . . . No soldier is obliged to obey an order that is contrary to the will of God…In the name of God then, in the name of this suffering people I ask you, I beg you, I command you in the name of God: stop the repression!”

Photo appeared in El País on 7 November 2009 with the information that the state of El Salvador recognized its responsibility in the crime.

On March 24th, 1980, one day after his sermon calling on the soldiers to not obey the military, Romero was giving Mass in a small chapel located in a hospital called “La Divina Providencia” for a funeral of someone who been murdered a week before. The chapel was full as always because of his newfound popularity. While raising the chalice at the end of the Eucharistic rite, a gunman shot him through the heart with a sniper rifle. His blood covered the altar and he fell, gasping for breath in front of the terrified crowd. He was dead within minutes.

According to sources, just before the bullets fell Romero, he uttered the words, “One must not love oneself so much, as to avoid getting involved in the risks of life that history demands of us, and those that fend off danger will lose their lives.”

Days before his murder Archbishop Romero told a reporter, “You can tell the people that if they succeed in killing me, that I forgive and bless those who do it. Hopefully, they will realize they are wasting their time. A bishop will die, but the church of God, which is the people, will never perish.” He added, “I do not believe in death without resurrection. If they kill me, I will be resurrected in the Salvadoran people.”

It is widely believed that the killers were members of a death squad trained by the United States. In an official report by the United Nations in 1993, it was announced that an army Major by the name of Roberto D’Aubuisson, a School of the Americas graduate with counterinsurgency intelligence experience, had ordered the killing of Romero. Captain Álvaro Rafael Saravia, who participated in the assassination, said the effort was led by D’Aubuisson. D’Aubuisson had publically spoken of the need to “take care” of the Archbishop, a statement which he made in the context of publically speaking of the need to kill 200,000 or 300,000 to restore order to El Salvador.

Years later, in the National Security Archive, scholars obtained a declassified document about a conversation with Roberto D’Aubuisson in which he bragged about planning the killing of Archbishop Romero, and in which he mentions a lottery between the members of his death squads in which the “winners” would be the ones to kill Romero. D’Aubuisson would found his own far-right party, the Nationalist Republic Alliance or ARENA, not long after the murder of Romero. ARENA would dominate the political scene in El Salvador until 1989.

Romero’s funeral was attended by 250,000 mourners, and was called the largest demonstration in El Salvador’s history. It was fired upon by army forces. Some who attended were shot down in front of the cathedral by snipers from the rooftops. Romero is considered the unofficial patron saint of the Americas and El Salvador. He is often referred to as “San Romero” or “Saint Romero” in El Salvador and throughout the world.

Despite this title, the Catholic Church has been reluctant to recognize the murdered priest, although they have beatified many less-deserving figures, as an essay by Dr. Michael Parenti points out:

“John Paul also beatified Cardinal Aloysius Stepinac, the leading Croatian cleric who welcomed the Nazi and fascist Ustashi takeover of Croatia during World War II. Stepinac sat in the Ustashi parliament, appeared at numerous public events with top ranking Nazis and Ustashi, and openly supported the Croatian fascist regime that exterminated hundreds of thousands of Serbs, Jews, and Roma (“gypsies”).

In John Paul’s celestial pantheon, reactionaries had a better chance at canonization than reformers. Consider his treatment of Archbishop Oscar Romero who spoke against the injustices and oppressions suffered by the impoverished populace of El Salvador and for this was assassinated by a right-wing death squad. John Paul never denounced the killing or its perpetrators, calling it only ‘tragic.’ In fact, just weeks before Romero was murdered, high-ranking officials of the Arena party, the legal arm of the death squads, sent a well-received delegation to the Vatican to complain of Romero’s public statements on behalf of the poor.

Romero was thought by many poor Salvadorans to be something of a saint, but John Paul attempted to ban any discussion of his beatification for fifty years. Popular pressure from El Salvador caused the Vatican to cut the delay to twenty-five years. […] In either case, Romero was consigned to the slow track.” (9)

The Four Women: the Rape & Murder of Missionaries

“My fear of death is being challenged constantly as children, lovely young girls, old people are being shot and some cut up with machetes and bodies thrown by the road and people prohibited from burying them. A loving Father must have a new life of unimaginable joy and peace prepared for these precious unknown, uncelebrated martyrs.” — Maura Clarke

“Christ invites us not to fear persecution because, believe me, brothers and sisters, the one who is committed to the poor must run the same fate as the poor, and in El Salvador we know what the fate of the poor signifies: to disappear, be tortured, to be held captive – and to be found dead.” — Ita Ford

“These nuns were not just nuns; they were also political activists.” — Ronald Reagan’s UN ambassador, Jeanne Kirkpatrick, on the rape and murder of the nuns.

On December 2nd, 1980, a few months after the assassination of Romero, four female missionaries were beaten, raped and murdered by members of El Salvador military. Jean Donovan, Maura Clarke, Ita Ford and Dorothy Kazel were charity workers who were under surveillance by the Salvadoran National Guardsman (La Guardia Nacionál) at the time. They had worked with refugees from the Salvadorian Civil War, providing them food, clothing, shelter and transportation to safety.

Dressed in civilian clothes and acting on orders from their commanders, five soldiers abducted the four at the airport and took them a remote spot where the rape and murder commenced. Peasants nearby heard the gunfire and saw the soldiers in clothes exiting the white van they had used for the abductions, and heard the radio blaring from it. The van would be found on fire at the side of the airport road later that night.

The next morning, December 3th, the peasants discovered the women’s buried and mutilated bodies. They were ordered by local officials and commanders to bury the bodies in a common grave. They did so, but then informed a local priest, and the word quickly spread. On December 4th, in front of fifteen reporters and the US Ambassadr to El Salvador, the bodies of the four women were exhumed from the shallow grave. The attempted cover-up had failed.

News of the rapes and murders sparked outrage after it was made public in the United States. The US pressured the El Salvador regime to investigate. It soon became clear that earlier investigations were nothing more than attempts to whitewash the atrocity. Of the five officers convicted of the rape and murder, three were trained at the United States School of the Americas.

The head of the National Guard, whose troops were responsible for the murders, Gen. Carlos Eugenio Vides Casanova, went on to become Minister of Defense in the government of José Napoleón Duarte.

“The [1993] U.N.-sponsored Report of the Commission on the Truth for El Salvador concluded that the abductions were planned in advance and the men responsible had carried out the murders on orders from above. It further stated that the head of the National Guard and two officers assigned to investigate the case had concealed the facts to harm the judicial process. The murder of the women, along with attempts by the Salvadoran military and some American officials to cover it up, generated a grass-roots opposition in the U.S., as well as ignited intense debate over the Administration’s policy in El Salvador. In 1984, the defendants were found guilty and sentenced to 30 years in prison. The Truth Commission noted that this was the first time in Salvadoran history that a judge had found a member of the military guilty of assassination. In 1998, three of the soldiers were released for good behavior. Two of the men remain in prison and have petitioned the Salvadoran government for pardons” (11).

The bodies of two of the women, Clarke and Ford, were not expatriated but buried in Chalatenango. The State Department charged the Fonovans $3,500 for the return of their daughter’s body.

EL SALVADOR. Santiago Nonualco. 1980. Unearthing of three assassinated American nuns and layworker from unmarked grave. (EL SALVADOR, page 63) ©Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

In his final days as president, Carter increased military aid to El Salvador to $10 million, and sent additional American advisors. This happened after the military took over the University of Central America. With the election of US President Ronald Reagan, President José Napoleón Duarte became a symbol of “anti-communist resistance” in Latin America. Soon after the rape and murder of the church women, the FMLN would fight back in 1981. For many years the El Salvador military government carried out more and more well-known torture and murder of innocents. The media in the United States did not breathe a word of criticism.

In 1982, Ronald Reagan would approve the standards of human rights in El Salvador. In 1983, he would ask Congress to send more aid to the government, even after one of the worst massacres Central America would know: El Mozote.

The El Mozote Massacre

“Death Squads are an extremely effective tool, however odious, in combating revolutionary challenges.” — Neil Livingstone, a consultant who worked with Oliver North at the National Security Council.

“Be a Patriot! Kill a Priest.” — Roberto D’Aubuisson’s death squad slogan.

“We don’t complain about them at all, they haven’t done any of those kind of things, it’s the military that is doing this. Only the military. The popular organization isn’t doing any of this.” — U.S. congressional delegation submitting a report to Congress.

The Carter, Reagan and Bush Administrations poured more than $4.5 – 6 billion in military aid into El Salvador during the course of the war, making it the second largest recipient of U.S. military aid next to Israel. The Reagan administration in particular boosted aid to the military junta to the tune of $32.5 million, which by 1986 was increased to $212 million. After the 1981 massacres, US military aid would continue unabated once again. Over 3,500 Salvadorian military officers, in other words nearly the entire officer corps, would be trained in US-operated facilities in country and in other countries such as Honduras. Many of these would later be implicated in atrocities.

In December of 1981, one of the most devastating acts of brutality in the entire Salvadorian Civil War would take place in the village of El Mozote and small neighboring villages. On the days of December 10th, 11th and 13th, the soldiers of the military’s American-trained Atlacatl Battalion murdered at least 1,000 civilian men, women, children and the elderly. The massacre was committed through shootings, hangings, grenades and decapitation.

The Atlacatl Battalion was an elite unit trained and equipped by the United States on March, 1981. Fifteen specialists in anti-communist counter-insurgency from the US Army School of Special Forces trained the Brigade. It was designed from the beginning to engage in mass murder. An American trainer remarked they were “particularly ferocious….We’ve always had a hard time getting them to take prisoners instead of ears.”

The mission was called Operación Rescate (“Operation Rescue”). It was part of the ostensibly “anti-guerrilla campaign,” but there were no combatants in El Mozote. The villagers were completely unarmed and were not even guerrilla sympathizers. The predominately Protestant villagers of El Mozote believed they were on good relations with the military and the government and thus ignored FMLN warnings to evacuate before the army swept through. Some of the victims of the massacre had even come to El Mozote from other villages to seek refuge from the killings perpetrated by the army and paramilitaries.

The murders were carried out in a calculated, systematic way – first, the men were separated from the women and children. The men were taken to several locations while being tied and blindfolded, where they were interrogated, tortured for information they didn’t have, and then executed. Around noon, the soldiers separated the older women and the children and divided them into groups. Most of the women were repeatedly raped before being murdered with machine gun fire. Girls as young as ten years old were raped. Hundreds of children were tortured and killed last. Little boys watched as their brothers were hung from trees. Some were herded and locked in the town church and shot through the windows.

From El Mozote there was only one survivor—Rufina Amaya Marquez, who lost her husband, Domingo Claros, who was decaptitated in front of her, as well as her three children. Her son Cristino, who was nine years old, yelled out to her, “Mama, they’re killing me. They’ve killed my sister. They’re going to kill me.” Her three daughters María Dolores, María Lilian, and María Isabel, ages 5 years, 3 years, and 8 months old respectively, were also killed. Amaya watched as they raped, tortured and killed villagers and afterwards burned their bodies. Her family and neighbors were killed. Rufina Amaya recounted her story many times for the press:

“An army officer who was a friend of her husband’s, she said, had told the villagers early in December not to worry about a coming offensive against the guerrillas, because El Mozote, which had a large evangelical population, was not known to be subversivo, or subversive.

The troops arrived the following day and, after an initial brutal search, told the villagers that they could return to their homes. ‘We were happy then,’ Señora Amaya recalled. ‘’The repression is over,’ we said. But the troops returned.

Acting on orders, they separated the villagers into groups of men, young girls, and women and children. Rufina Amaya managed to slip behind some trees as her group was being herded to the killing ground, and from there she witnessed the murders, which went on until late at night. An army officer, told by an underling that a soldier was refusing to kill children, said, “Where is the sonofabitch who said that? I am going to kill him,” and bayoneted a child on the spot. She heard her own children crying out for her as they met their deaths. The troops herded people into the church and houses facing a patch of grass that served as the village plaza. They shot the villagers or dismembered them with machetes, then set the structures on fire. At last, believing they had killed all the citizens of El Mozote and the surrounding hamlets, the troops withdrew” (Guillermoprieto). Afterwards, all the buildings of the village were burned and the bodies of hundreds of dead were disposed of or buried.

“As Amaya’s husband, Domingo Claros, was led away with another man, the two villagers broke into a run, attempting in vain to escape. Cut down by M-16 rifles, Claros and his partner were then beheaded by Atlacatl soldiers wielding machetes. The decapitations were two of many conducted that day by the soldiers. […] ‘First they picked out the young girls and took them away to the hills,’ where they were raped before being killed, Amaya reported. ‘Then they picked out the old women and took them to Israel Marquez’s house on the square. We heard the shots there.’ The children died last. ‘An order arrived from a Lt. Caceres to Lt. Ortega to go ahead and kill the children too[.]’” (16).

One child reported:

“’They slit some of the kids’ throats, and many they hanged from the tree … The soldiers kept telling us, ‘You are guerrillas and this is justice. This is justice.’ Finally, there were only three of us left. I watched them hang my brother. He was two years old. I could see that I was going to be killed soon, and I thought it would be better to die running, so I ran. I slipped through the soldiers and dived into the bushes. They fired into the bushes, but none of their bullets hit me’” (16).

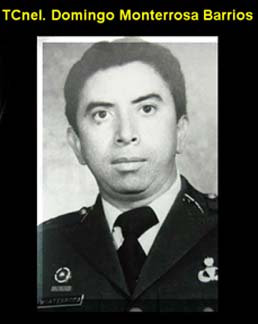

The soldiers who committed this massacre were not acting on their own, nor were they disobeying orders from above. On the contrary, such a massacre was directly ordered by Lieutenant Colonel Domingo Monterrosa Barrios, a School of the Americas graduate who was the commander of the Atlacatl Battalion. He was seen landing a helicopter in the vicinity of El Mozote before the mass murder. He was present during the operation and it was done on his orders.

Reporter James LeMoyne received the answer from Monterrosa:

“Yeah, we did it,” he said. “We killed everyone. In those days I thought that was what we had to do to win the war. And I was wrong” (14).

The Atlacatl Batallion and Monterrosa continued to be supported by the United States in El Salvador.

Reports of the massacre and photographs of the corpses appeared in the United States soon after in the New York Times and the Washington Post, reported by journalists Raymond Bonner and Alma Guillermoprieto, who visited the site of the massacre. The US government tried its best to cover up the event:

“The U.S. Embassy, after an aborted and cursory inquiry, reported that it had no evidence that an atrocity had happened. Washington then participated with its Salvadoran allies in covering up the massacre; in doing so it had the help of the Wall Street Journal, among others. Bonner was pulled out of the country by the Times soon after his articles appeared. U.S. policy toward El Salvador was not affected by news of the atrocity, and the Reagan administration routinely ‘certified’ to Congress that the human rights situation there was improving” (14).

The Reagan Administration sought to dismiss it as “communist propaganda” engineered by the FMLN. This became harder and harder to uphold however, when forensic evidence of the massacre, including the exhumed bodies of many children, emerged. A United Nations team dug up hundreds of skeletons. Soon after, the Washington Post published details on the actions of the Salvadorian army after El Mozote.

“Several months after the massacre, the Salvadoran army returned to the scene and collected the skulls of some El Mozote children as novelty items, the Post reported. ‘They worked well as candle holders,’ recalled one of the soldiers, Jose Wilfredo Salgado, ‘and better as good luck charms.’” (15).

Despite these reports, the Reagan Administration sought to discredit the reports and the journalists who made them. American journalist Mark Hertsgaard summed up the reasons behind the U.S. cover-up:

“What made the [El Mozote] massacre stories so threatening was that they repudiated the fundamental moral claim that undergirded US policy. They suggested that what the United States was supporting in Central America was not democracy but repression. They therefore threatened to shift the political debate from means to ends, from how best to combat the supposed Communist threat — send US troops or merely US aid? — to why the United States was backing state terrorism in the first place” (18).

Sources

[1] http://www.nytimes.com/1987/10/22/world/salvador-divided-over-aid-to-police.html?pagewanted=1

[2] http://www.math.dartmouth.edu/~lamperti/centralamerica_elsalvador.html

[3] Raymond Bonner, quoted in Encyclopedia of War crimes and Genocide, page 197-198.

[4] Wallechinsky, David, and Amy Wallace. The New Book of Lists: The Original Compendium of Curious Information. New York, NY: Canongate, 2005. 365.

[5] Chambers, John Whiteclay, and Fred Anderson. The Oxford Companion to American Military History. New York: Oxford UP, 1999. 246.

[6] http://www.thirdworldtraveler.com/Chomsky/ChomOdon_ElSalvador.html

[7] Rossiter, Caleb S. The Turkey and the Eagle: The Struggle for America’s Global Role. New York: Algora Pub., 2010. 69.

[8] http://onlineministries.creighton.edu/CollaborativeMinistry/romero-wp-3-28-80.html

[9] http://www.michaelparenti.org/motherteresa.html

[10] http://www.uscatholic.org/culture/social-justice/2009/02/oscar-romero-bishop-poor

[11] http://www.maryknoll.org/MARYKNOLL/SISTERS/ms_marty4ani.htm

[12] Guillermoprieto, Alma. “Shedding Light on Humanity’s Dark Side.” Washington Post, 14 March 2007, Print.

[13] Mark Danner, The Massacre at El Mozote. New York: Vintage, 1994, and Leigh Binford, The El Mozote Massacre. Tuscon: University of Arizona Press, 1996. Danner’s report was first published in The New Yorker magazine.

[14] http://www.math.dartmouth.edu/~lamperti/Trojan_Horse.html

[15] http://www.consortiumnews.com/2007/012907.html

[16] http://www.libertadlatina.org/LatAm_El_Salvador_El_Mozote_Massacre_1981.htm

[17] http://www.markdanner.com/articles/show/141?class=related_content_link

[18] Hertsgaard, Mark. On Bended Knee: The Press and the Reagan Presidency. New York: Schocken, 1989.

Categories: Colonialism, Economic Exploitation, El Salvador, Government, History, Imperialism, Imperialist War, International, Reactionary Watch, Revolutionary History, Theory, United States History, Workers Struggle, World History

Tell us Your Thoughts